Guidelines for Optimizing PCR: Concentration of Target DNA and Primers

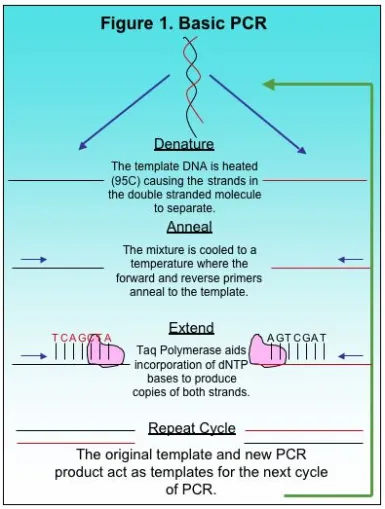

The Polymerase Chain Reaction, or PCR, is a basic method used in molecular biology to produce copies of a small target region of DNA in a sample. The basics to PCR were discussed previously here. The copies of DNA produced by PCR provide researchers with sufficient copies for other applications in research including automated Sanger sequencing. Although there is basic methodology to most PCR methods, each reaction is different and requires optimization, a process for adjusting variables and producing a single desired product. There are several factors to consider when optimizing PCR such as total copies of target DNA, primer concentration, MgCl2 and deoxynucleotides, or dNTPs. Some of these variables depend on the total volume of the PCR reaction because the final concentration of the components in PCR should be constant depending on whether the reaction is 25 ul, 50 ul or 100 ul. In this article we will focus on two variables, the number of copies of the target DNA and primer concentration.

The Template: Target DNA

Generating copies of a target DNA region using PCR applications is not as sensitive to the quality of the template DNA when compared to Sanger sequencing. However, it is still advisable to use a relatively pure DNA sample free from salts and other contaminants. Clean template DNA has a better probability to generate a clean PCR product. The final diluted sample of target DNA is better diluted in water rather than buffer because buffers can interfere with difficult PCR amplifications.

The most important aspect of the target DNA to consider is the total number of copies in the reaction available for amplification. The target DNA provides the initial template for the amplification of the first set of products amplified and continues to provide the template for the remaining cycles. As PCR products are generated, they also provide copies of the target DNA used as a template for amplification. This is what allows PCR to generate millions of copies of a target region. Therefore, it is important that sufficient copies of the original target DNA are present in the reaction. Too many copies of the original target can lead to generation of false products early in PCR that also act as template DNA. The template DNA isolated from bacteria may consist of only a 2 million-base genome whereas the human genome has 3 billion bases. Therefore, bacterial genomic DNA will have far more copies of the target in a 50 ng sample than human DNA. For bacterial DNA 10E5 copies will require only 300 picograms of DNA. For human DNA 10E5 will require over 300 nanograms of DNA, a one million fold difference.

PCR conditions generally recommend 10E4 to 10E5 copies of the target DNA in the reaction independent of the total volume. There is some flexibility in the copy number of the target sequence. However, more copies of the target DNA will reduce specificity of the PCR reaction and likely produce a greater number of false products. The total number of cycles for PCR should be reduced when higher concentrations of target DNA are in the reaction.

Concentration of the Primers

Primers are the determining factor of what region of the DNA will be amplified by PCR. The forward and reverse primer must have an exact base match with the beginning and end of the target region. Excessive primer concentration is perhaps one important factor that often causes generation of false products in a PCR. Too much primer reduces specificity and this will allow primers to anneal in regions of the template that are not the target region. The results of excessive primers are often seen in unclean Sanger sequencing results because false products can be sequenced along with the desired target. The amount of forward and reverse primer should be limited to reduce potential false priming. Excessive concentrations of forward and reverse primers can also cause formation of primer dimer when the primers anneal and amplify themselves independent of the target DNA.

Primer concentration is one variable dependent on the total volume of the PCR reaction in order that sufficient copies of the primer find the target annealing sites. A total concentration of 0.5 micro-Molar (uM) to 1 uM is generally sufficient to amplify most target regions, although a smaller concentration may also work in some applications. Typically our lab uses a final concentration of 0.8 uM for most PCR reactions. The final judgment on primer concentration will be viewed after products are electrophoresed on an agarose gel in order to show the number of products amplified.

We use a relatively simple calculation to dilute primers to a final concentration of 10 uM as shown starting with the primary primer concentration of 1 micro-grams (ug)/ micro-liter (ul). It requires that the molecular weight (MW) of the primer is known and should be provided along with the primer.

1 ug/ul *1umol/MW (ug) *10E6 ul/l = concentration umol/l which equals uM

A primer with the final concentration of 200 uM will be diluted by adding 1 ul of the primer to 19 ul of water for a final concentration of 10 uM. This is our working concentration for PCR. For a final concentration of 0.8 uM, 2 ul of the forward and reverse primer are added to a 25 ul reaction whereas 8 ul of each would be added to a 100 ul PCR reaction.

Primer concentration is one of the more important variables to consider when optimizing a PCR reaction. Concentrations greater than 1 uM could often lead to primers annealing along non-target regions and the generation of false products. Insufficient concentrations of either primer could result in little or no amplification.